Forster’s Tern in front, Caspian Tern in back, and Common Terns. Wisconsin, May 2023.

Common Tern and Forster’s Tern are subtle birds that create a lot of confusion for birders, especially in places like Chicago where we see them both in small numbers during migration. The field marks for these species are subtle and variable, however even when people put in time to learn the field marks, they may struggle if they don’t know what to prioritize.

There is already a great resource about Common vs. Forster’s in spring here:

https://ebird.org/mo/news/identification-of-common-and-forsters-terns-in-spring

What I’ve done here is to try and compliment the info that’s already out there with more photos, to highlight the few field marks that I find to be the most powerful, and to discuss what complications occur with these field marks. My experience comes mainly from the Wisconsin lakefront, where there are still a good number of these terns around each spring. All photos were taken in Wisconsin, May of 2023, unless otherwise noted. Remember, this is for spring birds – some of what follows is helpful year round, while some info does not apply to other times of year.

1 - The Forster’s Mask

The “Forster’s Mask” makes the top of the list. This is a plumage pattern that is unique in the Great Lakes region to immature and nonbreeding Forster’s Terns. A large percentage of the Forster’s Terns seen on Lake Michigan in the spring have some form of mask evident. Importantly, even if only the impression of this mask is apparent (see below), you can stop wondering — you almost certainly have a Forster’s Tern.

This head pattern gets called a “mask” rather than “cap” or “hood” because the dark areas on the sides of the face do not connect over the top of the head as in other terns.

The Forster’s mask outlined in yellow: solid dark behind and surrounding the eye, white behind the bill and on the forehead. This individual has some sparse dark around the back of the head.

Another angle. Compare to the adult terns below.

Adult Common above, adult Forster’s below, showing typical full caps. The cap shape is very similar in the two species, but there are subtle and variable differences, such as the size and shape of the white region behind the bill.

Forster’s Tern with solid dark mask and more extensive dark spotting around the top of head.

Many Forster’s Terns in spring look like the bird above: the mask region is solid dark, while the area over the top of the head is extensively spotted with dark. These birds probably include “second summer” birds, born a little less than two years prior, but may also be less advanced looking adults. Common Terns will pretty much never show this pattern at this time and place. Later in the summer, immature Common Terns show up with more confusing head patterns, but during migration in May on Lake Michigan, Common Terns will almost always show the full, solid cap as they are shown here.

Three Forster’s Terns. Left to right: immatures and probable adult. Note the impression of a mask on the left bird, which has diffuse dark wrapping around the back of the head, compared to the solid dark cap of the adult Forster’s on the right. Unlike with Common Terns, with Forster’s Terns we often see small masks, full caps, and everything in between in spring.

Photo: Don Estep, New Buffalo, Michigan. May 2023.

Two Forster’s Terns in flight. A less obvious mask (left) and more obvious mask (right). Note the appearance of a “dark wedge” on the wing of the bird on the left – this trait is more often associated with Common Terns, but is normal and often seen in immature Forster’s during the spring.

Forster’s Tern with dark mask and spotty dark around the top of the head.

Takeaway: the Forster’s mask is unique in the Great Lakes region, and even when subtly apparent, rules out any other tern species at any time of year. The vast majority of Common Terns on Lake Michigan in May show full, solid dark caps.

2 - Gray Body, White Body

All ages of Forster’s Terns have white bodies, while nearly all Common Terns seen on Lake Michigan in the spring have gray bodies. You would think that with this distinction, more people would look for this trait, yet in my experience people are more inclined to look at field marks such as wingtips and tail feather length, which are extremely variable or difficult to remember. There are a couple reasons why this might be.

One, the body shade field mark is temporary, and later in the year both young and old Common Terns can have white bodies just like Forster’s. Two, the difference in body shade can be subtle, and is especially obscured by direct sunlight.

Soft lighting, like that from overcast skies, or ambient light created by overhead sun, is best to assess body shade.

Body shade in sitting birds.

Forster’s Tern in front, Caspian Tern in back, and Common Terns.

Looking at the Forster’s Tern in the photo above, you will see that it looks darker underneath, but that is due to shadow. It is actually uniformly white from its face all the way down to its underside. The Common Terns on the other hand, are white on their faces just below the cap and then fade to gray somewhere on their lower head and chest. Because the upper chest is not in shadow, looking for contrast between the face and chest can help determine whether the body is gray or white.

Common Tern on the left, Forster’s on the right. Checking for contrast between the white area on the face and the upper chest can be helpful, especially in soft light.

Common Terns in direct sun.

Direct, hard light can complicate the body shade field mark considerably. More intense highlights may be confused with white plumage, while more contrasting shadows may be confused with gray plumage. Finding a Forster’s Tern among these Common Terns without using other field marks is difficult.

Two Forster’s with Common Terns. The white underparts on the center Forster’s are obvious with the right lighting. The mask on the young Forster’s on the left of the frame is also obvious.

Forster’s in front with Common Terns. Notice the lack of contrast between the white face and the white chest on the Forster’s. This is an immature Forster’s showing an incomplete cap and darker wing coverts.

Body shade in flight.

Forster’s Tern above, Common Tern below, overcast.

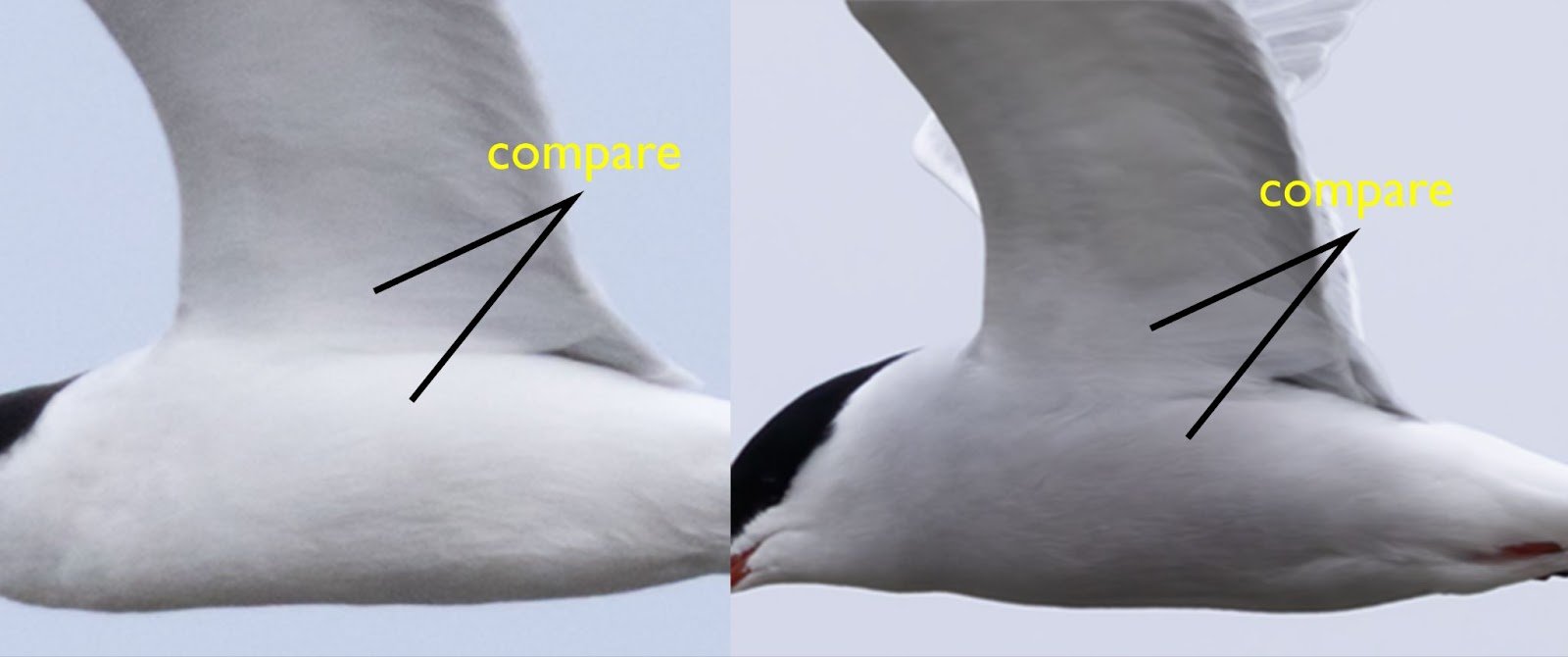

If you only have one or a small number of birds to look at, comparing the side of the body to the underwing can be helpful. Both species have white underwings that are usually darkened by shadow. The side of the body of the Forster’s Tern appears subtly paler than the underwing due to this shadow, whereas the side of the Common Tern shows either a darker shade or a similar dark gray to the underwing.

Forster’s Tern left, Common Tern right.

Two Forster’s Terns (lower left with wings raised, and lower middle with wings lowered) with Common Terns, overcast. Note how the uniform white body on the lower Forster’s Tern has a different look from the gray-bodied Common Terns, which have darker bodies than their underwings.

One Forster’s Tern (lower middle, wings raised) with Common Terns, overcast.

Forster’s Tern above, Common Tern below, in hard light from a low sun. As with sitting birds, direct sun makes it difficult to discern differences in plumage from differences due to reflection and shadow. Here you can also see a subtle difference in the underwing on the outer primaries; Common Terns have less dark that is more discrete, while Forster’s have more diffuse dark that goes farther up the inner webs.

Forster’s Tern above, Common Tern below, with high, midday sun. While the upperparts are shining from the direct sun, the underparts are all in shadow. The difference between the body shade and underwing can be discerned in this case.

Takeaway: Forster’s Terns have white bodies, while Common Terns in spring have gray bodies, with very few exceptions. The main difficulty in discerning this difference comes from direct, hard lighting, but in most cases this is an important field mark.

3 - Bare Part Color

Common Tern left, Forster’s Tern right. Note the different bill and leg color between species. The bill color of the Forster’s stands out a little more than the leg color.

The color of the bare parts, including the bill and to a lesser degree the legs, are useful at closer distances. One complication is that some individuals of both species show variably dark bills in the spring; this is the norm in immature birds, but even some birds with mature plumage (full dark caps, for example) show mostly dark bills in May.

Forster’s Tern with dark bill and dull orange legs, with Caspian Terns and Ring-billed Gull.

New Buffalo, MI, May 10, 2023.

The same Forster’s Tern in flight.

Two Forster’s Terns on the left, showing typical yellow-ish orange bill base compared to the more red bills of the Common Terns.

Takeaway: bare part coloration, particularly the bill, is useful when the color is present, however bills can be variably dark during the spring.

4 - Upperwing

The Forster’s Tern you want to see:

The Forster’s Tern you see:

The Common Tern you want to see:

The Common Tern you see:

In a nutshell, wingtips in terns are a mess. Note that all of these images are taken within a few days of each other in May, and are accurate representations of what one might actually observe in the field, with little editing on Photoshop etc. While the plumage itself is highly variable in spring Forster’s Terns, the appearance of the upperwing in both species is altered drastically by lighting. It is useful to understand a unique feature of tern primaries:

“The dorsal surface of the outer primaries in many species (of tern) has a distinct frosting or silvery bloom when fresh, caused by elongated, curved, and frilled barbules on the distal sides of the barbs; when the barbules wear off, underlying black becomes conspicuous, such that fresh primaries are paler and grayer and worn feathers are darker and blacker dorsally.”

-from Pyle, intro to tern section

In other words, the primaries on these birds are paler when fresh and darker when worn, the exact opposite of what happens in most feathers (including the gray body feathers of Common Terns!). When you see contrasting dark outer primaries, as on the second Forster’s Tern above, it means that some span of time elapsed between the growth of those dark outer primaries and the growth of the fresher inner primaries, during which time the older feathers wore away their “silvery bloom.” Tern molt is a complex topic that varies with species, age, and even individuals of the same species and age (!). All this means is: expect variability in tern wings.

Common Terns, overcast.

Most Common Tern adults in spring do not yet show heavily contrasting dark outer primaries. Many show a dark indent midway through the wing, but this is not obvious on many individuals, with the impression instead being a mostly uniform gray upperwing. The dark tips to the outer primaries, visible on the upper- and under-wing, are also shown by many Forster’s Terns.

Some immature Forster’s Terns show many dark primaries in the spring, which is why you should always look for a “Forster’s mask” before giving any weight to a dark wingtip.

Forster’s Tern with heavily worn, dark primaries and a couple fresh, pale inner primaries from a more recent molt.

Other Forster’s have a more advanced look, with less worn primaries and nearly complete dark caps:

Forster’s Tern with more moderate wear in primaries in May. The cap is more advanced on this individual, being nearly completely dark but with a small gap behind the bill (more visible in other photos). Note the duller primaries and some older, worn wing coverts. At a distance, the pale body is probably a more obvious indicator of the species, followed by the build and perhaps the paleness of the secondaries and primary coverts. This is the same individual from the fifth photo in the “Gray Body, White Body” section.

Forster’s Tern with very little wear to the outer primaries.

One Forster’s Tern (lower middle) with Common Terns.

This Forster’s Tern shows little wear, with contrasting pale outer primaries, along with pale primary coverts and secondaries. Compare with the more uniformly gray upperparts of the Common Tern. These differences are most apparent in soft lighting. Note the darker, more worn outer primaries on the highest Common Tern, compared to the more uniform primaries on the individual to the lower right.

Forster’s Tern left, Common Tern right. Even with the rather dull primaries on this Forster’s Tern, it has a less uniform upperwing, with contrasting pale primary coverts and secondaries. At this angle and distance you can also make out the gray tail contrasting the white rump on the Forster’s Tern, compared to the all white tail of the Common Tern.

Forster’s Tern above, Common Tern below, direct sun. Adding glare from direct sun with variable wear of primaries, the most reliable difference between the upperwings may be the pale secondaries on the Forster’s vs. the thin pale-edged secondaries of the Common Tern – and this is not very obvious. Again, body shade is probably a more powerful field mark in this situation, especially without direct comparison.

Takeaway: upperwing plumage is highly variable in appearance due to variable molt, wear, and lighting conditions. This creates many situations where differences between species are not obvious. Upperwing field marks are useful to know, but should be used with caution and an awareness of complications.

5 - Build

Build deserves a mention. Even though it is variable within each species and takes experience to learn, it can be surprisingly useful, especially when dealing with large numbers of birds.

Forster’s Terns average larger bills and heads, longer necks, and relatively thicker bodies. Common Terns have smaller fronts (head+neck+bill) and tend to have thinner bodies. Watching Common Terns flying all day and then seeing a Forster’s Tern fly in, it appears the body of the tern is swollen. The difference in body structure is more apparent in moving birds, i.e. in real life and videos. The differences in bill, head, and neck can be picked up on in many of the photos of sitting birds shown here.

On top of normal variation, keep in mind that a few fish in the belly can certainly change the shape of a bird.

A very well fed Common Tern.

Takeaway: build is variable and subtle, but can be a very helpful supporting field mark, especially with direct comparison of species. Feeding can alter the body shape.

6 - Other things

These field marks appear at the end not because they are not useful, but because they are either highly variable, require more experience to learn, or are so subtle that they require being very close or photographs to discern. As with any tricky ID, it is best to learn as many field marks as you can and then expect to use only some.

Sound - great, just need to learn the calls and build a memory.

Leg length - fine, just need to learn and build memory. Great if the two species are standing next to each other. Within-species variation can be confusing.

Outer tail feathers, length - highly variable in spring, but especially useful in the case where you see fully formed Forster’s tail feathers stick out behind the folded wings of a standing bird.

Outer tail feathers, dark outer web on Common vs white on Forster’s - difficult to discern unless close or with photos.

Shape of white behind bill - many, but not all mature Forster’s show an angled notch in the white behind the bill which is noticeable at a moderate distance or with photos – surprisingly useful.

Gray tail and white rump of Forster’s - useful in close flying birds that happen to show upperside, more obvious in soft light.

Amount of dark in bill tip of breeding adults - average differences exist, but much variability and transitional birds with dark bills in spring.

Shape and size of bill - Average differences are there, but are pretty variable within species. Confusing without a good memory or side-by-side comparison.

Underside of outer primaries in adults - with close view or photographs, more discrete dark tips to outer primaries of Common Tern vs. diffuse dark on Forster’s.

This bird has relatively short outer tail feathers (one is shorter than the other) with what appears to be prominent dark in them. In the field, would you be able to tell which web of the outer tail feather was dark? The primaries appear relatively dull compared to other parts of the upperwing. The above points may lead one to Common Tern, but this bird has a thick, uniformly white body; this is certainly a Forster’s Tern. The more yellowish-orange bill and paler secondaries are also in line with Forster’s. This is the same individual as the last Forster’s in the “Upperwing” section, three photos back.