“The story, as laid before us in the records of three thousand years, is fascinating and absorbing in its human interest for those who content themselves with the study of its countless personal incidents and neglect its profound philosophical lessons. But for those who study it in the scientific spirit, the human interest of its details becomes still more intensely fascinating and absorbing.”

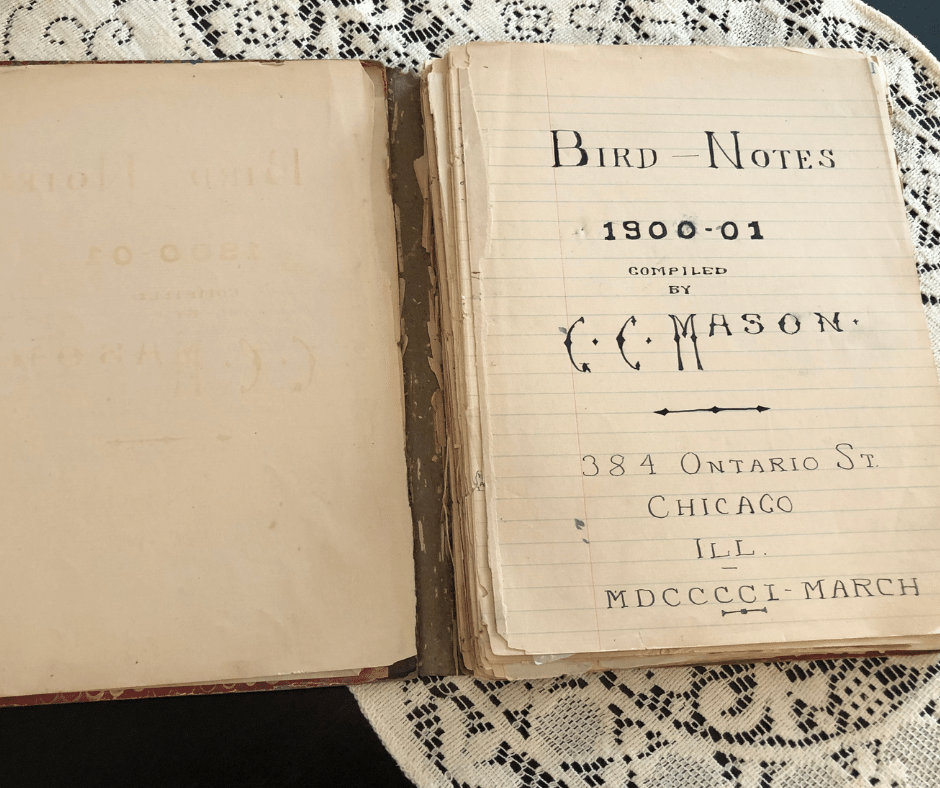

It begins like this, with John Fiske’s words scrawled in someone else’s delicate cursive on the endpapers of a journal. The quotation has been copied from Fiske’s book, The Beginnings of New England, and his words greet me with wonder as I struggle to make them out. What I am holding in my hands is not “the records of three thousand years,” but it is old, and it is a record. Turning the page, the title jumps out at me, inked in bold: Bird Notes: 1900-01. Turning the page again, and I am thrown headlong into a nearly 100-page birder’s journal kept by a then fourteen-year-old George Carrington Mason, son of Edward and Julia Mason, grandson of Roswell B. Mason, the mayor of Chicago during the Great Chicago Fire.

Knowing these small facts make the journal feel sacred, but I’m not entirely certain what I expect to find as I read through its yellowed and crumpling pages. Am I looking for exciting scientific insight into the world of Chicago birds during the start of the 1900s, or is there something more to be learned here? What can a beginning birder born towards the end of the 19th century have to teach me, a young woman so alive and on fire with the technology and plugged in-ness of the 21st? I feel entirely separated from him by this vast rift of time, and yet as I sift through the entries, I begin to recognize parts of myself—the young birder inside of me, and the writer who has her own collection of personal journals, books that span a lifetime cataloging not birds, but maybe not not birds, also.

*

George Carrington Mason was born in 1885 in Chicago, one of thirteen brothers and sisters. He grew up to be a shipbuilder and naval architect who eventually went on to receive his bachelor’s degree in Agriculture. With this degree, Mason became the forester of the Mariner’s Museum in Virginia where he helped to cultivate the flora and fauna surrounding the museum. He started an herbarium there and filled it with natural species growing in the area. A picture I have of him depicts him as an older, dignified man in his suit and tie. He wears a pair of oval spectacles that give him an inquisitive look, but despite his formal attire, there is a curiosity in his eyes, a particular way of looking.

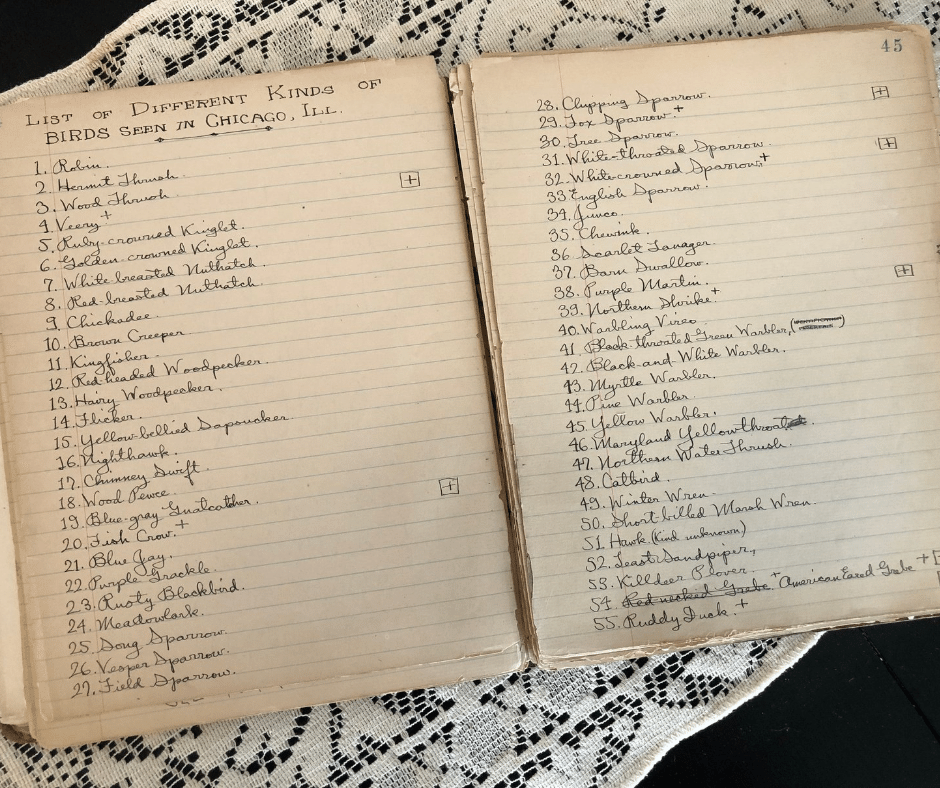

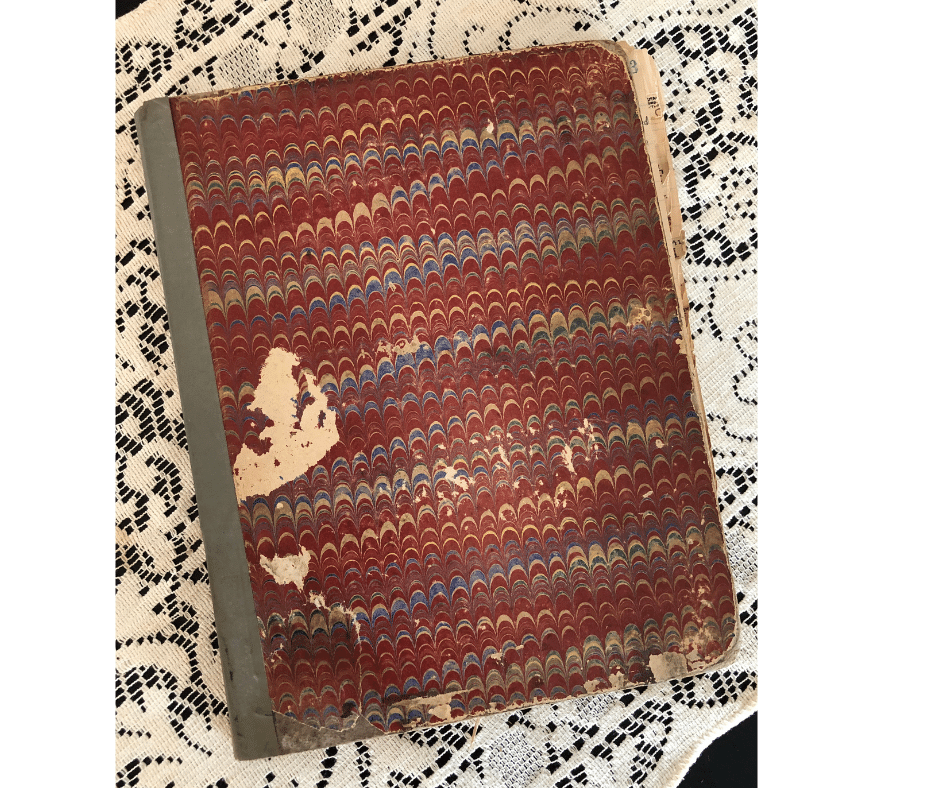

The journal, in contrast, is falling apart. Nearly all of the pages have come loose from their binding, and the spine is held together with a long piece of grey tape. Some of the pages are beginning to flake off into tiny shards of paper, and when I handle the book, I do so delicately, cradling each page as if I am holding a rare decomposing leaf. Even so, the fragility of the journal does not impede what Mason has recorded here. For over a year, he has dutifully logged all of the birds he has seen in Chicago, Illinois and Delavan, Wisconsin. The first entry, which is dated “April 5, 1900,” describes the day’s birds as “one blackbird (probably rusty or crow blackbird) and three or four juncos, besides the usual large number of herring gulls ‘bedded’ on the lake off the Lake Shore Drive at Bellevue Place.” In the margins, he has gingerly drawn a tiny depiction of a junco, along with a map detailing the empty lots where most of Mason’s birding takes place. “This entry marks the beginning of this season,” he notes, and I think about how young I was at fourteen. By the journal’s time, in six days, Mason will turn fifteen on April 11, and there will be absolutely no mention of it in these pages. It seems this is a place designated for science and observation only. Still, small details of Mason’s life do manage to slip in from time to time.

Most of Mason’s birding takes place in the early morning or on his walks home from school. Sometimes he is accompanied by one of his siblings—Norman, Ethel, and Fred are all mentioned—and once he even adds in a detail about his “mama” who “saw the tanager in the trees across the street again.” However, despite the occasional company, Mason is often alone in his expeditions, charting each phoebe, woodpecker, sparrow, and tern he comes across. He is rarely emotional in his detailing of the birds he sees, but on one morning “before breakfast” where he watched least terns through a telescope, he writes, “They flew up and down nearly all day, leaving for the south west about sunset and gave me altogether one of the best bird times in my existence.” His reasons for birding are never made clear in the pages of this journal, but I suspect his obsession started because he simply liked watching them. He was drawn in by the mystery that all birds seem to possess, a secrecy that seems to suggest their wingedness goes hand in hand with divinity.

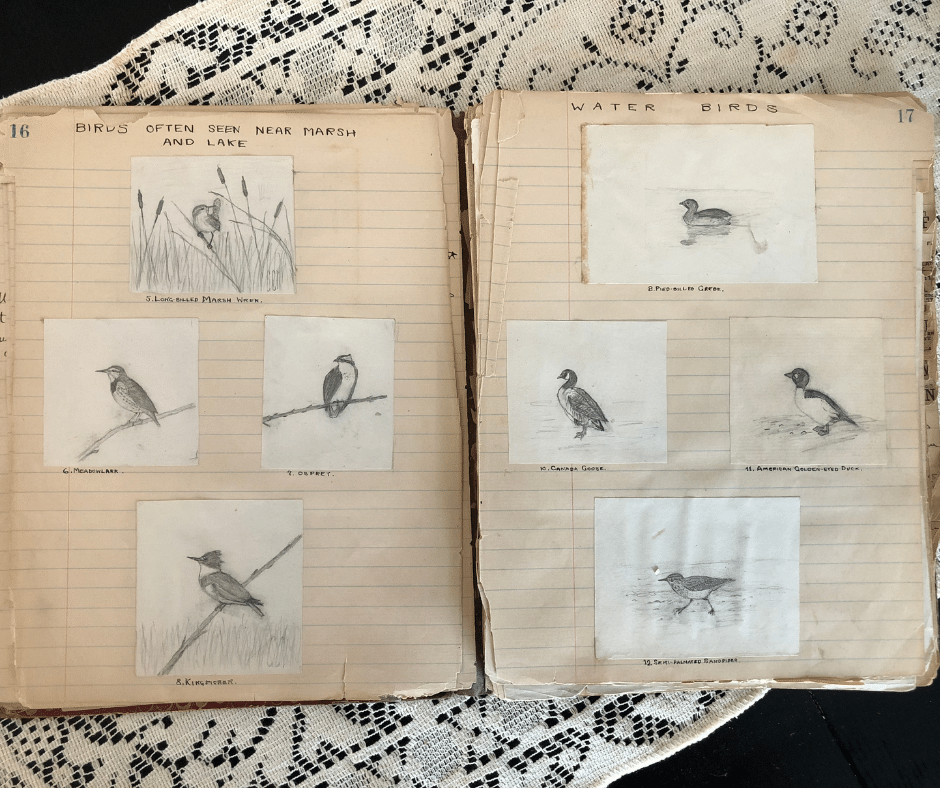

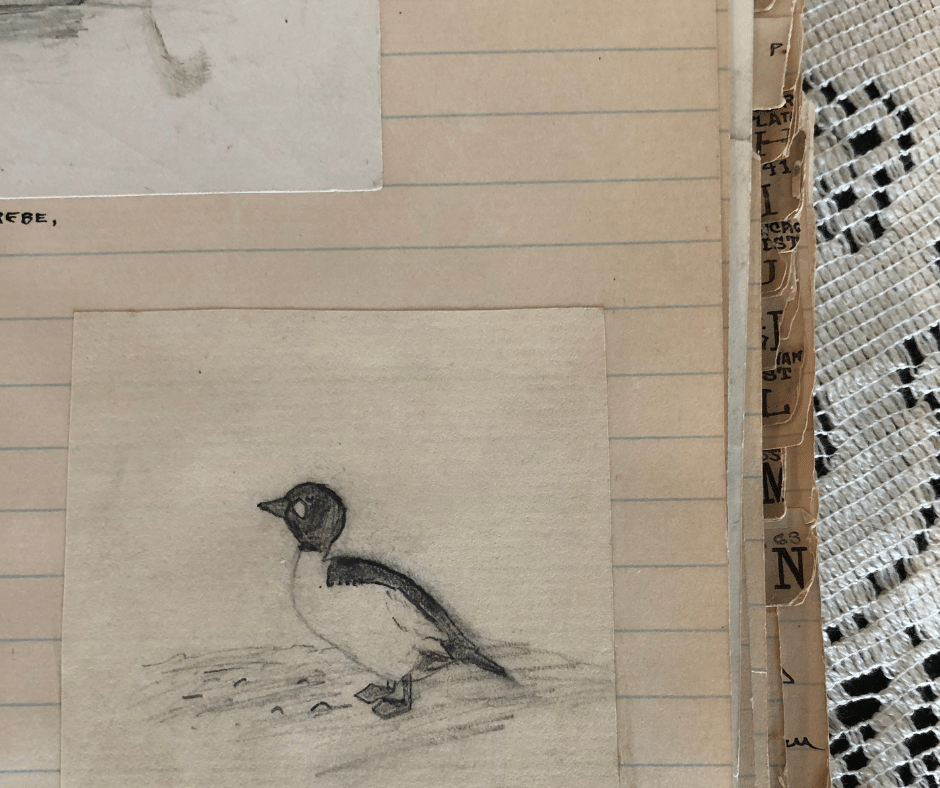

Mason’s journal came to the Chicago Audubon Society from the hands of his granddaughter, Elisabeth “Bitsy” Mason who wanted the journal to find a final home within archives devoted to birds and nature. In an e-mail, she describes her grandfather as having a “kind and gentle nature,” and she recognizes “what passion he put into” this record. She details bits of his life and explains that alongside his many accomplishments, “he was also a very good photographer and illustrator.” His drawing skills are displayed in the journal through a series of hand drawn sketches of birds that Mason copied from various books and glued onto a handful of early pages. There are long-billed marsh wrens and ospreys, grebes and chipping sparrows, kingbirds and chickadees. Each pencil sketch is small, taking up not nearly as much space as a standard Post-It, but the detail is impeccable. The marsh hawk floats above a sea of prairie grass. Tree sparrows perch on a delicate branch. Later, his illustrations become even more detailed as Mason begins to incorporate color. In these later drawings he is fascinated with the warblers, sketching them with fine lines and utmost care. The yellow winged warbler has a note next to its identifier that states the drawing was done “free-hand and partly original.”

Even so, for all of Mason’s enthusiasm, he was still a young ornithologist and therefore prone to making mistakes. Oftentimes, bird names are crossed out and renamed in pencil—signs that Mason saw the journal as a working record of the knowledge he was accumulating out in the field. Reading his corrections reminds me of Louisa May Alcott’s journals. She, too, saw them as more than just a recording of her days. Edited over and over again up until her death, the beloved author of Little Women understood that a journal could eventually become a reflection of herself. By editing it as she aged, she would be able to control her narrative long after her death. Mason may not have been thinking this intentionally as he recorded and revised bird after bird—after all, how was he to know that a 31-year-old woman would be reading and writing about him over a century after his birth? Still, his desire to correct his mistakes is telling, suggesting a dedication to accuracy both for himself and for future readers.

*

I have kept journals on and off for the majority of my life. The earliest ones are bound in composition notebooks covered in glittery stickers. I recorded my days in them, detailing the small nuances of someone who wasn’t even a decade old. In contrast, the journals I kept during my teen years are more expressive, filled with the angst you might expect from a young girl in the throes of adolescence. Currently, the journal I keep is more of a workspace than a diary. It is filled with my thoughts, but it is also a place to collect ideas and bits of information that I find useful or interesting. Still, despite these many attempts at cataloging my life, I have never managed to keep a daily account for longer than a few months. I get tripped up in the details, afraid that I’m not recording my experience exactly as it happened. The writer Sarah Manguso says in her book Ongoingness: The End of a Diary that “the diary was [her] defense against waking up at the end of [her] life and realizing [she’d] missed it.” I share this fear, but I’m also uncertain how to record myself wholly and with accuracy.

Mason’s birding journal is not a personal account of his life, but it does give us a glimpse of the kind of person he would grow up to become: studious, observational, and deeply in tune with the natural world and its many wonders. Each bird he recorded has the feeling of a moment in time captured in amber. None of the birds he observed during his outings are remarkable. They are what you would expect to see in the Chicago area back then and even today. Still, they feel precious because they were seen, spotted amongst the bushes and the trees, a fleeting vibrancy that helped educate and propel a young man down his rightful path. Here, I am reminded of Anne Lamott and her bird-centric metaphor for writing in her book Bird by Bird. For her, “bird by bird” is about taking things one step at a time, and surely Mason does this throughout his journal. But perhaps “bird by bird,” can be representative of something more, as well. Perhaps we can see it and this journal as a pillar against time. Discernable things we can point to in order to better understand our history. When I think of it like this, it doesn’t matter if I record the minutiae of my days exactly. Not every moment is a bird worth identifying. But for those that are, it is worth it to name them, write about them, sketch them in colored pencil and paint.

On May 5, Mason writes, “after dinner, I saw a solitary song sparrow with a covetous cat watching it,” and I picture him as this cat, doing his best to stand still in vacant fields and along the lakeshore as he searches the sky for birds. He is covetous in his desire to name as many as he can. If we think of the moments in our life like birds, perhaps we, too, can become this “covetous cat,” observing our memories, those birds, not so we may catch them and keep them, but so we can create a record of them to look back upon from time to time, presciently learning from them how to be.